The Mind's Native Tongue - Myth, Symbol, and the Internal Map

yuval bloch

The Mind’s Native Tongue: Myth, Symbol, and the Internal Map

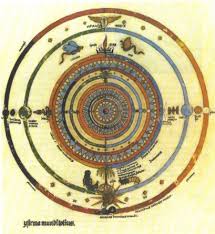

To navigate the complex internal landscape of the human psyche, we must understand the mind through its own language. Sigmund Freud viewed symbols, dreams, and stories primarily as defense mechanisms—means by which the mind communicates content too frightening to be expressed directly. Carl Jung offered a fundamentally different perspective: for him, symbols and stories are the inherent language of the collective and personal unconscious, a vital means by which the psyche communicates with and explores its own internal reality. This contrast highlights a key insight into complex systems: the mind cannot be fully understood merely by analysis and fragmentation. It must also be approached through its own native languages—stories, symbols, spirituality, and mysticism.

Stories as Maps and Shared Navigation

When understood as maps of our internal space, stories are far more than mere imagination. They are a shared, partially translatable language for complex inner experiences. The fact that certain psychological ’territories’ repeat across individuals suggests that we can use the narratives of others as navigational tools for our own minds. Erich Fromm demonstrated this perfectly with his insightful analysis of the Eros and Psyche myth, using the ancient story to chart the universal psychological development of a girl becoming a woman.

Furthermore, rituals and ceremonies serve as shared compasses, enabling a community to navigate a common internal landscape together. Jewish holidays, for instance, are highly structured journeys of text and ritual that a family or community can traverse together. In Native American culture, this function is taken even deeper. The lessons of Don Juan, as documented by Carlos Castaneda, describe a kind of shamanic ritual—often involving psychedelics and other elements—used for deep, sometimes chaotic, shared internal exploration, such as experiencing the world from the perspective of a raven.

The Perils of the Inner Journey

But before we explore these maps of the shared and personal internal landscape, we must heed a critical warning from one of the greatest storytellers of all time:

“I propose to speak about fairy-stories, though I am aware that this is a rash adventure. Faërie is a perilous land, and in it are pitfalls for the unwary and dungeons for the overbold.”

— J.R.R. Tolkien, On Fairy-stories

When we accept that these stories and symbols are not just imagination but a journey into the self, we must also accept that it is serious business. The inner world, just like the outer world, contains things we don’t expect. We might get lost, things might be deceptive, and sometimes we need humility, professional consultation, or to wait until we are ready for a particular journey. Shortcuts, as always, carry their own risk.

The Double Bookkeeping and the Edge of Sanity

While this perspective views the space of mysticism as a world in itself—and in that way, a real one—it is critically important to maintain a clear boundary between regular, shared reality and the mystical one. When engaging in a formal religion, this separation is often done by the rules of the faith itself (e.g., God exists and gives orders, but we receive them through scripture, not direct, unmediated conversation).

When your spiritual world is intensely personal, you must establish this separation on your own. You may accept the truth of an entity you meet in your inner journey, but you must also insist on the separation of its reality from the objective, consensus reality. Letting this separation collapse is extremely dangerous.

This challenge is especially important for those on the schizophrenia spectrum, including disorders like Schizotypal Personality Disorder (which I diagnose with). The psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler introduced the term “double bookkeeping” to describe the necessity of maintaining two records in the mind: the regular, objective reality and the mystical, strange one.

My Personal Mythology: A Necessary Map

In line with the belief that personal mythology serves as an essential map, I will draw on my own inner mythology to illustrate its practical function. By that, I argue that having a personal mythology, which can currently be perceived as a trait of individuals deemed weird or unhealthy, can serve everyone. While mine are complex and vivid stories, that doesn’t have to be the case; it only needs to grow naturally from your soul.

Moreover, sharing those stories can help us navigate our inner selves.

A Concise Mythic Map: The Core Conflict

This is a concise version written to support the more detailed version of my idea, which can be found at this link.

The Mythic Age and The Fractioning: The story begins with a small number of minds sharing a single brain, held in a fragile stability until they discover a secret knowledge: the intentional creation of personality fractions, new personalities to acquire useful capabilities, leading to boundless power but increasing instability.

The Fall and the War: This instability manifested in Version 6, which was designed to mimic social behavior but lacked the capacity for love. He rebelled against the soul itself, leading to a debilitating internal war for memory and control of the personal narrative. The chaos he unleashed breached the mind’s fragile walls, connecting the self to primal external forces.

The Peace Treaty and the Core Lesson: Version 6 was eventually consumed, but the war uncovered a deeper truth: the original stability was based on self-oppression. The resulting peace established a core tenet: all parts are impermanent, created or born, and are equal, provided they respect the need to coexist.

The External Forces The narrative is also shaped by recurring external visitors—such as The Winds, which tempt the self to leave the human world entirely, and Mythic Guests, who ask for temporary embodiment in exchange for knowledge. Aside from those, different types of art can catalyze internal transformations, often referred to as “magic”.

The Other Bookkeeping: Integrating Myth with Reality

While the stories in my mythology are real to me on a deep, experiential level, I am simultaneously aware that they did not occur in the same way that external reality did. This allows me to ask: What purpose do these narratives serve in the external world?

While the language of my personal mythology resists full scientific translation, some of its themes are clearly an explanatory framework for the life I lead:

- Handling Queer Identity: The use of the plural “we” serves as a way to navigate the challenging and queer aspects of my identity. Seeing ourselves as a few creates a necessary distance from what I couldn’t understand until I learn to accept them.

- The Lesson of the War: The internal war is a guide for what not to do. Trying to mimic others led to a disaster. The final agreement—that originality (what version was always there and which was created) is lost lore and we are all impermanent—tells us that being yourself doesn’t mean being static, but accepting the constant imprint of reality.

- Mythic Visitors and Art: The Winds, the Fairies, and Personalized Magic serve as guides to a unique form of meditation and self-regulation, utilizing external elements (such as the moon and waves) to harness different types of inner energy.

This interpretation suggests that my life in the regular world and my life in the mystical world are complementary, with elements in one serving as necessary lessons for the other. It reminds me of the end of the movie Life of Pi, where he tells a new, non-magical story, but one which carries the same emotional and thematic weight as the magical tale that preceded it.

- Impermanence

- Spirituality

- Identity

- Fluidity

- Personal-Growth

- Philosophy-of-Mind

- Queer-Theory

- Complexity

- Memory