Thanos's Flawed Premise: A Deeper Look at Population and Resources

yuval bloch

In Avengers: Infinity War, the villain Thanos offers a drastic and brutal “solution” to a universal problem: halve the population to prevent resource scarcity. While his methods are fictional, his reasoning echoes a real historical debate on the relationship between population growth and resource availability—a debate with deep intellectual roots.

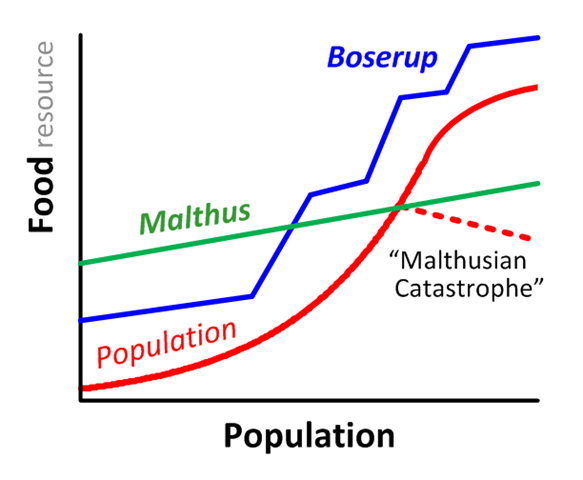

The first systematic exploration came from Thomas Malthus in his 1798 Essay on the Principle of Population. Malthus argued that human populations grow exponentially, while the resources needed to sustain them—especially food—grow only linearly. This imbalance, he warned, would inevitably push societies beyond their limits, leading to famine, disease, and conflict—what he referred to as “positive checks” on growth. His preferred solution was preventive checks: delayed marriage and smaller families.

What Malthus Missed: Innovation and Scarcity as Drivers

Since Malthus’s time, the global population has grown from roughly 900 million to nearly 9 billion—a tenfold increase. Yet food production has not only kept pace but often exceeded demand. This reality challenges Malthus’s prediction and forces the question: What did he overlook?

The core flaw in his theory was the omission of the role of human innovation. Malthus assumed resource production rates were fixed, but as economist Ester Boserup argued in 1965, scarcity can be a powerful motivator. Population pressure can spark agricultural breakthroughs—from improved irrigation to mechanized farming, synthetic fertilizers, and genetic engineering. In many cases, more people have meant more problem-solvers.

Boserup also observed that growing populations encourage labor-intensive, land-efficient practices—a process called agricultural intensification. This allows more food to be produced on the same land area, countering the Malthusian idea that population growth inevitably requires more farmland. In fact, the forest transition theory suggests that while early population growth may drive deforestation, later intensification can enable forest recovery as agricultural land use contracts.

The Complex Reality: Beyond Food Production

Innovation has so far kept the Malthusian catastrophe at bay, but the picture is more complex than simply disproving Malthus.

- The Jevons Paradox: Efficiency gains can sometimes lead to increased total consumption. A more fuel-efficient car may encourage longer drives, resulting in increased overall fuel consumption. Similarly, more efficient agriculture can lower food prices, driving higher demand and environmental strain.

- Uneven Development: Technological progress is not universal. In some regions—particularly parts of Africa—rapid population growth has outpaced innovation, resulting in localized famines and ecological degradation, reminiscent of the collapses of the Maya or Easter Island.

The Malthusian Paradox

From 1960 to the present, the world’s population has nearly tripled, yet the average daily calorie supply has increased from 2,360 to 2,944 kcal per person. We now produce more then enough to feed everyone. The real causes of hunger lie in distribution failures, inequality, and political instability—not in a global food shortage.

Still, recent shifts in agricultural productivity show why this success can’t be taken for granted.

Agricultural Productivity’s Troubling Trends

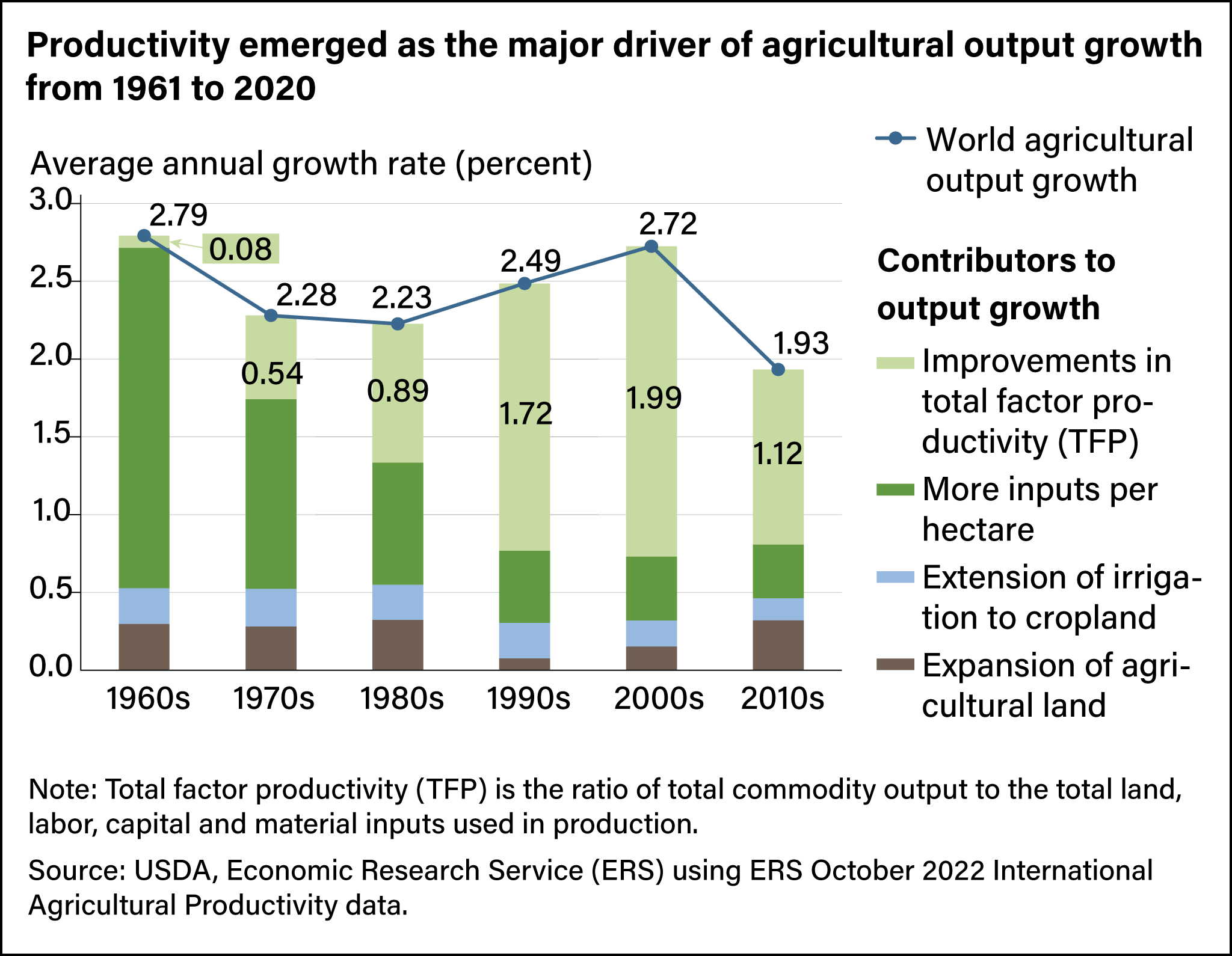

The Global Agricultural Productivity (GAP) report highlights a concerning shift in the drivers of food production.

1960–2010: This period saw a decline in the intensification of land use, as much of the world had already adopted intensive agricultural practices. Still, as Ester Boserup’s theory predicted, innovation—measured as Total Factor Productivity (TFP)—rose sharply to meet the demands of a growing population. As the reliance on intensive techniques (such as increased use of fertilizer or water) decreased, TFP growth took its place, closing the gap and preventing a food crisis.

2010–2020: A new trend emerged. Growth in both intensive techniques and TFP slowed, as current technologies approached local performance limits. This slowdown reduced the pace of overall food production gains and led to a troubling rise in land use, increasing environmental pressure. The GAP report notes that global TFP growth averaged just 1.14% during this period—well below the target required to sustainably feed the projected future population. Climate change, which disrupts production, is further contributing to this decline.

A System Under Stress

Although the slowdown in food production growth is still less pronounced than the slowdown in population growth—driven by cultural shifts and greater gender equality—and global output remains more than sufficient to feed everyone, the interaction of these trends with major global events has made our economic and political systems behave as if we were facing a true Malthusian crisis.

The FAO Food Price Index has registered sharp spikes in recent years, largely triggered by external shocks: droughts in politically unstable regions, the COVID-19 pandemic, biofuel subsidies diverting crops from food to fuel, and the war in Ukraine. These disruptions have fueled severe volatility in the agricultural sector, which in turn has ignited political instability, civil unrest, and breakdowns in food distribution—ushering in a new wave of challenges for global food security. Worse still, this turbulence has begun to undermine production itself, creating a vicious cycle in which shocks weaken supply, volatility deepens, and fragile systems grow ever more brittle.

Ironically, even with enough food to meet global needs, this volatility—driven more by economic and political fragility than absolute scarcity—resembles the very crisis Thomas Malthus warned of. Our true vulnerability lies not only in potential production limits, but in the fragility of the systems that deliver food where it is needed most.

looking forward

What happens next is difficult to predict. Will Boserup’s optimism be vindicated again through innovations—from algae-based proteins to insect farming, from genetic breakthroughs to robotics? Many promising avenues could accelerate productivity.

Alternatively, change could come through a cultural revolution in eating habits, such as a shift toward predominantly vegetarian diets, alongside slower population growth.

Still, two things are clear: for now, we remain far from a true Malthusian crisis, and radical measures like strict population control are unnecessary. Yet the risk of crisis has increased significantly over the last decade. Ignoring it would be a mistake—sustained global attention must focus on innovation in food production, efficient distribution, elimination of waste and effective distribution , rather than fighting over the food we already have the capacity to produce.

Sources

Boserup, Ester. The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change Under Population Pressure. London: Allen & Unwin, 1965.

Jevons, William Stanley. The Coal Question. London: Macmillan, 1865.

Malthus, Thomas Robert. An Essay on the Principle of Population. London, 1798.