Rent-Seeking, Complexity, and the Fall of Empires

yuval bloch

The Long Shadow of Babylon

The idea that an empire’s fall can be anticipated is not new. Over 2,500 years ago, Daniel’s prophecy foretold the rise of four beasts from a chaotic sea—each representing a great empire destined to dominate and then decline. His message was clear: Babylon’s reign would not last, nor would any that followed.

This historical pattern has been repeatedly affirmed. But why do empires fall? Why has no civilization sustained supremacy forever? In this post, I will explore two powerful, complementary theories that explain this recurring cycle of rise and collapse, then examine them in a journey through history.

This is a natural follow-up to my earlier post, Asimov’s Foundation Revisited which explored Asimov’s imaginary future theory of “psychohistory” and its prediction of the galactic empire’s end.

Measuring the Arc of Empire

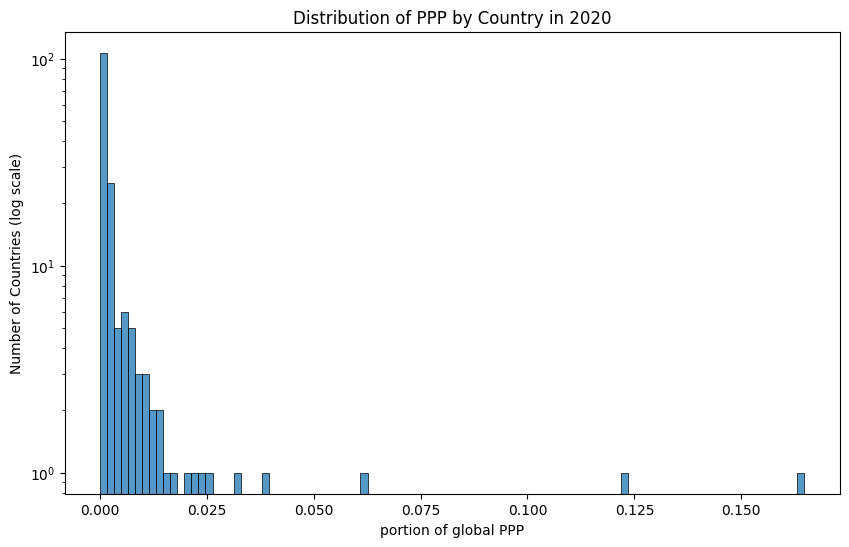

For this analysis, I utilize measurement of each civilization’s share of the global economy using purchasing power parity (PPP), which allows for more accurate comparisons across centuries. The data comes from the Maddison Project and Our World in Data, cross-checked against other historical sources.

Resources:

-

Maddison Project Database This dataset from the University of Groningen covers historical GDP and population data, including PPP (Purchasing Power Parity) for various countries.

-

Our World in Data: Global GDP over the Long Run This page visualizes and summarizes global GDP and economic size across history, using data from the Maddison Project.

How Empires Rise: Power Laws and Positive Feedback

A glance at the 2020 PPP data reveals a familiar pattern: a few countries dominate, while most remain small. This long-tailed distribution isn’t the result of chance; it reflects a “rich get richer” dynamic. Early advantages in geography, trade, or military capacity can trigger self-reinforcing growth—a phenomenon seen across complex systems from ecosystems to scientific citations.

In empire-building, early momentum compounds: more territory brings more wealth, which funds more armies, which secure more territory. In theory, such a system could grow without limit. In reality, history tells us that empires always peak, and the peak is strikingly consistent.

The Limits of Dominance

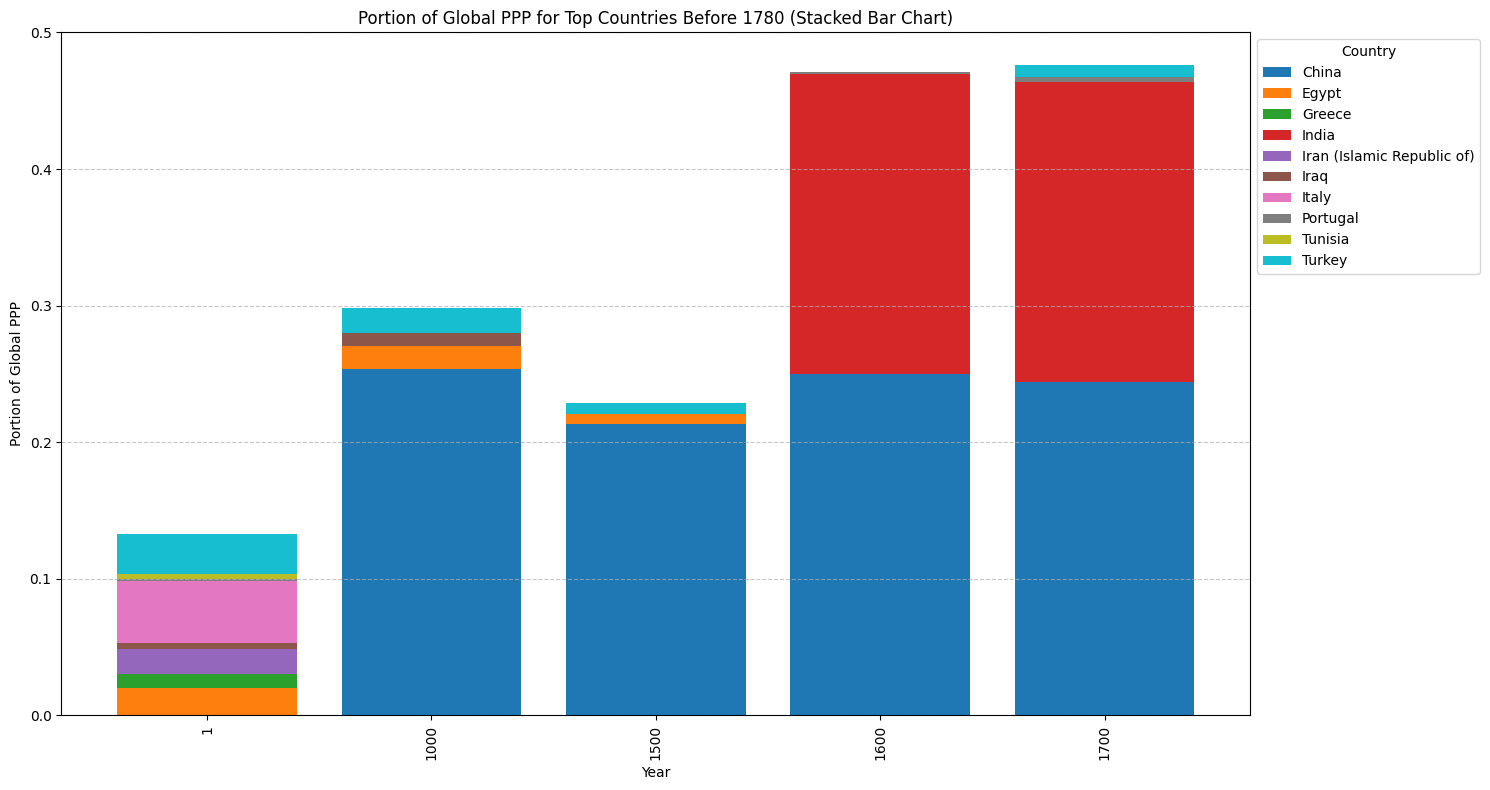

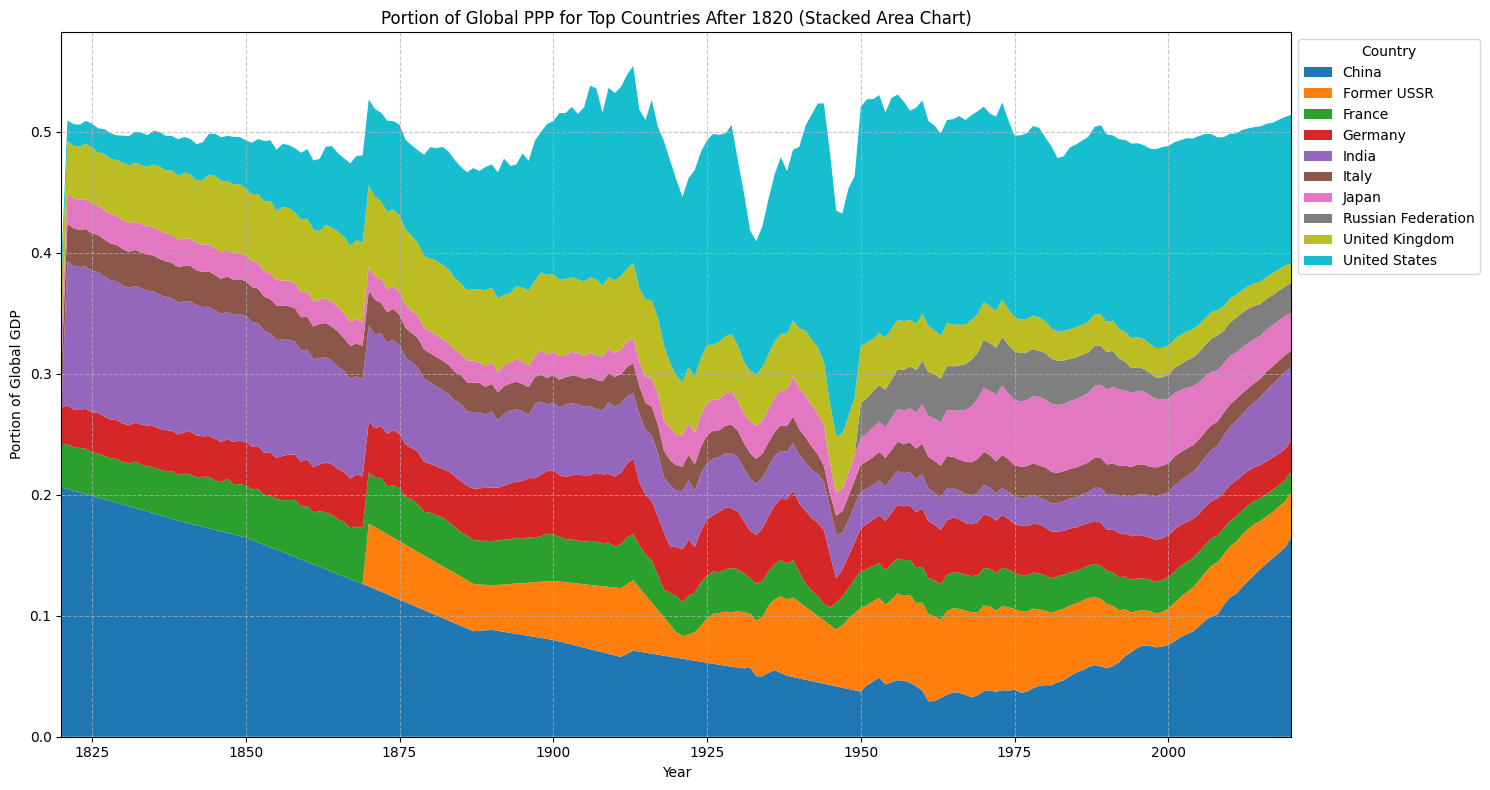

Even across wildly different cultures and technologies, no empire in the last two millennia has sustained more than roughly 15–25% of global PPP for long. Whether Rome, Song China, the Mughals, Britain, or the United States, the trajectory is similar: rapid ascent, a plateau within that range, then gradual or sudden decline.

Why? Two complementary theories help explain this recurring pattern.

-

Rent-Seeking and Internal Decay During the early expansionary phase, wealth flows into the empire through conquest, trade, and innovation. The elites who drive this phase—merchants, generals, inventors—are outward-looking, bringing in new resources and ideas. But as frontiers close, opportunities for external gain diminish. Power shifts to those who can extract wealth from within—bureaucrats, court elites, and political operators. These rent-seeking groups build systems to preserve their privileges, often blocking innovation and reform. Competition turns zero-sum, and the state becomes less an engine for expansion and more a prize to be fought over.

-

Complexity and Fragility In his work on societal collapse, Joseph Tainter argues that small states are simple, with few layers of governance. As an empire absorbs others, complexity grows: emperors over kings, kings over governors, governors over local officials. Initially, this complexity brings benefits, including better defense, integrated markets, and shared infrastructure. But each new layer adds costs. Eventually, the benefits of added complexity no longer outweigh the burdens—more taxes, more administration, more inefficiency. When this happens, citizens become overburdened, and the system faces “rapid simplification,” often breaking into smaller political units.

External Resources

A Journey Through History

The Roman Empire: Strength from the Frontier

The Roman Empire was characterized by multiple elite classes: the landed aristocracy, the merchant elite, and the military elite. In the early days of the Republic, each group had access to sources of power and wealth beyond Rome’s borders. Landowners could boost agricultural productivity with innovative techniques. Merchants tapped into the vast Mediterranean network, opening new trade routes. Military commanders earned riches through conquest, distributing plunder to their troops in exchange for loyalty.

By the first century CE, however, those external opportunities had dried up. Provinces were more valuable for their tax income than for discovery. The noble class turned its focus inward, vying for high-ranking government positions. Meanwhile, military commanders, unable to gain prestige through foreign conquest, began to seek power from within. This shift sparked internal competition, civil wars, and rampant corruption. As the empire became less a vehicle for expansion and more a prize to be seized, it ultimately collapsed under its own weight.

Song China: The Scholar-Elite’s Paradox

Nearly a millennium later, Zhao Kuangyin, the founder of the Song Dynasty, was acutely aware of the danger of ambitious generals. To prevent the warlordism he had witnessed firsthand, he curtailed the military elite’s power and established a new ruling class of scholar-officials, selected through rigorous civil service examinations.

At first, this strategy worked. The scholar-bureaucrats focused on internal development, technological innovation, and cultural flourishing. Under their stewardship, China experienced remarkable growth, eventually accounting for 24% of the world’s GDP (PPP). The institutional system it built endured for centuries, and China remained the world’s leading economic power until around 1700.

Yet the seeds of decline were already planted. Over time, success depended less on genuine merit and more on mastering the nuances of Confucian philosophy and the stylistic preferences of examiners. This fostered a vast and lucrative exam-preparation industry. Wealthy families could secure advantages for their sons, turning the scholar-official class into a de facto corporate elite. Once entrenched, this elite used its position to extract immense wealth—often ten to fifty times their official salary through corruption. To preserve the status quo, the exams focused more on rigid structure and less on creative content, creating a generation of conformist officials who lacked the creativity vital to lead their country in a changing world.

*External Resources: Pass or Perish: China’s Ultimate Exam

The Mughal Empire: Proto-Global Prosperity Derailed from Within

Mughal India boasted a thriving proto-industrial economy. By the 17th and early 18th centuries, it accounted for roughly 25–28% of global industrial output, primarily due to the production of textiles, shipbuilding, and ironworking. This placed Mughal India among the world’s economic giants. However, wealth did not translate into sustained innovation or inclusive institutions. As elites drew power inward, the nation became fractured, making it easy prey for the newly rising British Empire.

The British Empire: The Cost of a Grand Social Game

After taking control of India from the Mughals, the British Empire’s wealth grew significantly, fueling widespread corruption within the East India Company. This new wealth intensified competition among the elite. This competition often manifested in extravagant displays of status, such as competing for higher-status marriages, luxurious clothing, and lavish balls—the kind of scenes we see in shows like Bridgerton. The resources once used for expansion and improving farming and trade were now diverted to these zero-sum social competitions. The empire’s ruling class became increasingly concerned with preserving its social standing and less with the empire’s long-term health.

The USA: The Power and Limitations of Private Enterprise

Like the Song dynasty before it, the USA has a unique trait built to safeguard it from the fate of all empires: decentralization. By placing power in private hands, the system ensures that when corruption takes hold in one company, it can be replaced, keeping the entire system safe.

Armed with this power, the USA rose to new heights between 1944 and 1970,with 50% of nominal GDP and 25% of global PPP. During this period, it landed a man on the moon, rebuilt West Germany, and led to the creation of NATO.

However, no one is safe. After 1970, companies became experts in using subsidies and regulations to suppress competition. The growth of the financial sector found a way to create fast gains, causing the 2008 crisis, while politicians focused on polarization to gain power. While the USA still has economic power, with 22% of nominal GDP and 14% of PPP, it is much less than it used to be.

*External Resources Economics Explained: The Rise and Fall of the USA

Conclusion: Lessons from the Long Arc of Empire

From Rome’s marble forums to Washington’s marble halls, the rhythm is the same: rise through outward ambition, peak within a narrow band of global dominance, and decline as internal competition and complexity overtake expansion, those was only of few examples, when so many other empire see the same or worst destiny.

Daniel’s prophecy may have been theological, but its underlying truth endures: no empire is eternal. The fall is not a matter of if, but when—and how. Understanding these cycles doesn’t just illuminate the past; it sharpens our awareness of the present. The lesson for smaller nations is clear: do not stake your future on a single hegemon. For investors, the same logic applies—corporate dominance follows the same curve. The rich get richer… until they don’t.

📬 Subscribe

💡 Essays on life, chaos, and the quiet order beneath it all. Get them by email—about once a week