Chaos Theory of Human Hubris: From Jurassic Park to Afghanistan

yuval bloch

I came across Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park by chance. The school I attended as a child had limited physical resources, and its small library didn’t offer many books. With so few options, I often ended up reading whatever I could get my hands on, even stories that didn’t immediately grab my interest. Jurassic Park was one of them.

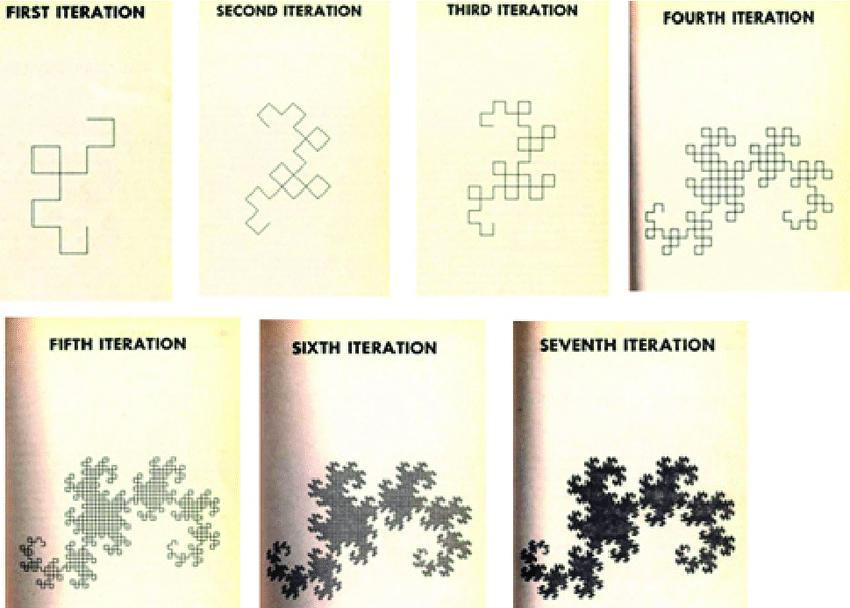

Unlike the movie, which is remembered mainly for dinosaurs devouring people, Michael Crichton’s novel is about something deeper: chaos theory, complex systems, and the limits of human control. The book is divided into “iterations,” each beginning with a quote from Ian Malcolm about chaos theory. Every chapter opens with a fractal diagram that becomes more intricate as the story unfolds—mirroring how the park itself unravels, shifting from apparent order into uncontrollable chaos.

At first, I found these digressions tedious. But over time, they fascinated me. I still remember the ending vividly: a Costa Rican warplane dropping napalm on Isla Nublar. After all the intricacy and unpredictability, the human response was brutally simple—burn it down.

That instinct—to reach for overwhelming force when complexity exceeds our understanding—is not confined to fiction. It characterizes much of human history. Systems collapse when treated as predictable machines, yet instead of learning, we often respond with escalation.

This pattern is clear in modern wars. The U.S. invasions of Iraq and Afghanistan began with simple plans: remove hostile regimes and impose order. But both quickly spiraled into chaotic, unpredictable struggles against insurgencies and fractured societies. Like the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park, these systems refused containment. And again, the human response was the same: more troops, more bombs, more force.

Time Scales of Complexity

Both ecological systems and wars operate across multiple time scales, each shaped by different dominant processes. What seems predictable at one scale becomes chaotic at another.

Ecological Systems

- Short-term (years): Seasonal cycles dominate plant–pollinator networks.

- Medium-term (centuries): Migration and demographic shifts become more important.

- Long-term (millions of years): Evolution and adaptation reshape entire ecosystems.

Some systems appear linear at short scales but chaotic over longer horizons; others do the opposite, aggregating into stability when viewed broadly.

Wars

Wars follow a similar pattern:

- Short-term: Tactical outcomes depend on the availability of soldiers, weapons, supply lines, and effective command structures. These can often be modeled semi-predictably.

- Medium-term: Production, alliances, and external interventions matter more than single battles.

- Long-term: Adaptation and technology fundamentally reshape the conflict, altering the rules of war itself.

Adaptation in Conflict

The war on terror illustrates this long-term dynamic of adaptation.

During the First Lebanon War, Hezbollah initially relied on simple explosive traps. Israel countered with technology to neutralize them. Hezbollah adapted again, using remote electronic devices. Israel responded with electronic detection systems. Finally, Hezbollah shifted back to simpler, non-electronic methods—forcing Israel to adapt once more.

Adaptation isn’t only technological. The Taliban learn fast to use social media not just as propaganda but as a weapon of psychological warfare—spreading fear and rallying allies with a speed state armies struggled to match.

Speed of Adaptation

Nation-states are large, complex organizations with extensive supply chains, factories, and rigid command hierarchies. While this allows for sophisticated, large-scale strategies, it also slows down decision-making. For example, the Afghanistan Papers, a collection of interviews conducted by the Pentagon to document lessons from the war, revealed a significant flaw: it could take the U.S. command structure years to identify a strategic problem, revise the plan, and implement a change. This was often delayed further by political considerations, as commanders were sometimes reluctant to report failures up the chain.

By contrast, decentralized groups like terrorist organizations adapt almost instantly. If one squad finds a tactic that works, others copy it immediately. If it fails, the innovator often dies with his mistake. This brutal efficiency allows rapid evolution in the field.

Biological Parallels: Phages and Bacteria

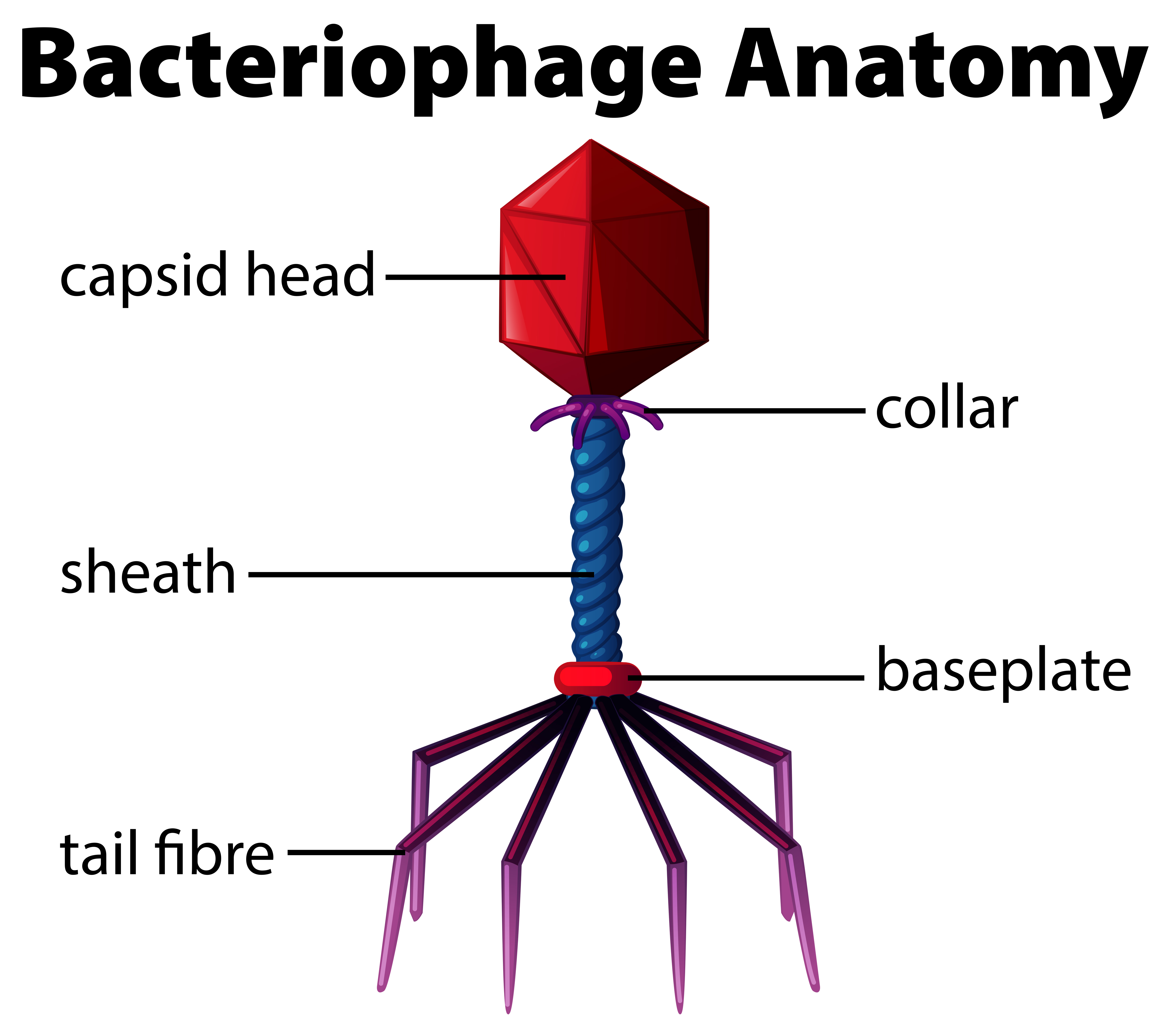

This asymmetric adaptation is well known in biology. Phages—viruses that infect bacteria—mutate quickly to exploit bacterial defenses. Bacteria, being more complex, evolve more slowly but with a broader range of strategies. Most of the time, bacteria suppress phages. But occasionally, a phage finds a weakness and spreads explosively, devastating bacterial populations.

History shows similar dynamics between empires and tribes. Rome dominated Gaul for centuries, yet tribal groups could sometimes exploit weaknesses and inflict major defeats. The same applies in counterterrorism: powerful states achieve dominance most of the time, but prolonged wars give smaller groups windows to strike effectively.

Conclusion: Lessons in Humility

Modern nations often approach counterterrorism as if it were a logistical task—predictable, linear, solvable by force. This can work in the short term. But as wars drag on, systems grow more complex, less predictable, and harder to control.

The instinct is to escalate—more force, more firepower. Yet chaos theory and history both suggest that brute force is often the least effective tool at this stage. Decentralized adaptation, local power balances, and the ability to adjust quickly become just as important as military might.

The obvious solution is to avoid long wars, achieving what’s possible quickly and preparing for future, distinct engagements. When that’s not possible, we must abandon the hubris of control. We must accept that not every problem can be solved with force and that a willingness to adapt faster and a tolerance for internal criticism of strategy are as important as the size of your army. In the end, Crichton’s warning is clear: the most dangerous thing in a complex system isn’t the chaos itself, but the delusion that we can control it.

further read

nice summary of the Afghanistan papers by the Washington post