Building Worlds: Why Our Realities Diverge

yuval bloch

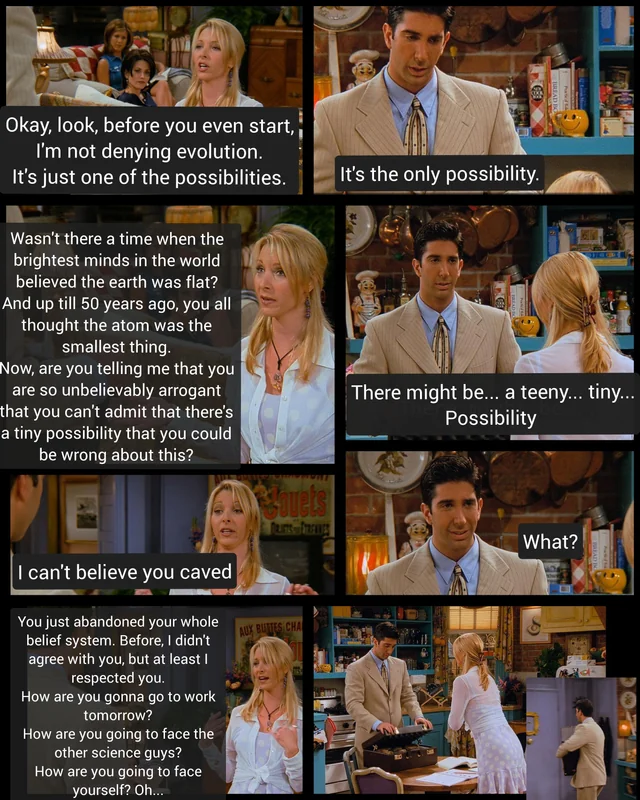

It’s easy to feel that people who hold beliefs contradicting well-established facts are unintelligent. We’ve all met individuals who, despite overwhelming evidence, remain steadfast in their convictions. However, upon closer inspection, it often becomes clear that these individuals are far from unintelligent. This apparent paradox prompts a deeper examination of how we construct our understanding of reality and how people with similar cognitive abilities can arrive at vastly different conclusions.

Perhaps most importantly, it leads us to ask: How can we ever be sure we’re right?

This question extends beyond individual minds to society as a whole. What conditions foster the widespread acceptance of accurate information? And what kinds of environments allow misinformation and falsehoods to spread and take root?

What Does It Mean to “Know”?

Let’s start with a brief philosophical detour. If “knowing” means holding facts about the ultimate true nature of the world, then we must admit we know very little. René Descartes famously sought a foundation of certainty, arriving at:

“Cogito, ergo sum” — “I think, therefore I am.”

The act of thinking cannot be doubted; from this, he concluded his existence. But this tiny island of certainty is far from enough to understand the complex world we inhabit.

So, let’s adopt a different, more functional definition of knowledge. We don’t necessarily need to know the ultimate truth; we need to make accurate predictions. Whether we’re trying to stay warm in winter, improve a relationship, or split atoms, what we call “knowledge” is a mental model—an imperfect yet useful representation of reality that allows us to anticipate what will happen next.

In this sense, knowledge is a coherent set of beliefs that consistently align with our past experiences and, more importantly, produce accurate and successful predictions. This is the working definition of knowledge we’ll use moving forward.

How Do We Acquire Knowledge?

At the core of knowledge lies a fundamental assumption: the future depends on the past. If our understanding aligns with everything we’ve experienced so far, it’s likely to remain consistent with what lies ahead. This assumption is essential but not sufficient. Even when accounting for all our experiences, countless ways exist to construct a model that fits them. To choose among these possibilities, we rely on another well-established principle, supported both mathematically and through personal experience: Occam’s razor. The simplest model that explains all the observations we’ve made so far is the one most likely to yield accurate predictions.

Based on this, one might imagine that two intelligent individuals who trust each other could easily reach an agreement, even on complex questions. After all, they only need to share their experiences and construct the simplest model that explains them all. However, this isn’t how we actually build knowledge. We can’t think of everything we know all at once. Instead, we interpret and update our understanding gradually, as each new observation comes in, always aiming to maintain internal coherence.

More importantly, the decisions we make depend on our current knowledge, and in turn, those decisions shape the experiences we encounter. This feedback loop reveals a key insight: in dynamic learning systems like ours, the order in which observations are made matters. Even if two people ultimately witness the same events, a slight difference in early experiences can lead to profoundly different worldviews.

This sequential nature of learning has also inspired innovations in artificial intelligence, such as curriculum learning, where AI systems are intentionally trained on ordered data, often moving from simpler to more complex examples. A particularly fascinating line of research in this area involves training AI for visual classification using images captured from cameras mounted on babies’ heads. These “headcam” studies aim to understand how our unique, egocentric view of the world in early life might influence our learning processes and shape our fundamental understanding of objects and causality.

This kind of dynamic also lies at the heart of many popular cultural forms—for example, the detective genre. In these stories, you follow the detective step by step, often arriving at a perfectly reasonable yet completely wrong conclusion. Then, suddenly, a simple explanation emerges—one that makes sense of everything. These narratives often begin by gathering evidence that subtly points in the wrong direction. As more clues appear, you interpret them through the lens of your initial conclusion, reinforcing it, until you cannot see the obvious solution that appears until the end.

Key Conclusions So Far

To summarize what we’ve discussed, two key conclusions emerge. First, a person’s worldview is shaped not only by their intelligence, and obsevations but also by the order in which they’ve experienced and interpreted events. This means that encountering someone with a very different perspective doesn’t imply they are irrational or unintelligent. Second, this does not mean that all worldviews are equally valid. We can evaluate the quality of a worldview by how well it predicts future events—how often its expectations align with reality.

Now that we have established this vital understanding, let’s address one of the primary challenges of the 21st century: the rapid spread of misinformation.

Modeling Misinformation and Polarization

Let’s now consider a specific type of conclusion: the reliability of a source. In many situations, what others say is our primary means of accessing truth. This raises a crucial question: how do we decide whom to trust?

When someone tells us something we believe to be false, we face two possible options:

- We can assume that they are right, and therefore revise our belief about the fact itself, along with any related belief.

- Or, we can maintain our original belief and instead update our judgment of the person’s reliability, lowering our trust in them as a source, or even stop seeing them as friends.

Many researchers use network-based models to investigate how beliefs, trust, and information co-evolve. In these models, nodes represent individuals, and edges encode perceived trust or credibility between them—essentially, how much one person considers another a reliable source of information. When this model evolves, one belief updates based on the belief of its connection, but also its connection updates based on differences in belief.

While these models might begin with random or fully connected networks, by the end of their simulations, they reveal the emergence of a range of observed social dynamics, including:

- Echo chambers: Individuals form tightly connected groups that reinforce shared beliefs while filtering out opposing views.

- Polarization: The population splits into two or more ideologically extreme camps with little interaction between them.

- Fringe clusters: Small groups that develop and sustain niche or unconventional beliefs, often isolated from the mainstream.

- Power-law distributions in belief popularity: A few beliefs gain widespread adoption, while many others remain marginal.

- Faster and more persistent spread of misinformation: False or emotionally charged content tends to propagate faster but also disappear faster, creating short waves of dominance

- Sensitivity to initial conditions: Early interactions and trust patterns can strongly influence long-term belief structures and social division.

These models also allow researchers to investigate how altering specific parameters affects these outcomes. From their insights, we can derive two crucial strategies to help reduce misinformation and polarization:

- High Tolerance for Disagreement: When individuals remain open to interacting with others who hold differing views, it helps prevent the formation of echo chambers. This preserves cross-group communication, promoting a more integrated network where both accurate information and corrections to falsehoods can circulate effectively.

- Self-Criticism: While expecting consensus can quickly spread accurate information, an low level of self-criticism, especially when combined with a low tolerance for disagreement allow fast spread false information to dominate and then stabilize within fragmented groups. A sound level of self-criticism is crucial in avoiding this pitfall, enabling us to question even trusted sources while still distinguishing them from untrusted ones.

The Bigger Picture: Cultivating a Complex Worldview

In all my blogs, I explore how complex systems theory can profoundly affect our worldview. By fostering a more nuanced and less simplified way of thinking—one that discourages quick assumptions—we can promote a range of positive outcomes, including peace, self-acceptance, and resilience.

This post continues that direction. It encourages us to resist the urge to dismiss those with different beliefs as unintelligent. Instead, it urges us to continue listening, even to those with whom we strongly disagree, and to maintain a healthy level of critical thinking toward all sources, including those we trust. This approach is essential to navigate the complex landscape of information without succumbing to the dangerous notion that all truths are relative.

it’s only a taste of this fascinating area of science that becomes vital as time goes by and we will revisit this subject in future posts, asking questions like how different media promote reliable and unreliable information